Wai Kai’s goal is to ensure its future is managed with deep respect for the history and traditions of Hawaii.

Hoakalei is home to three preservation areas with oversight provided by the Hoakalei Cultural Foundation: the Kauhale, Ahu and Kuapapa Preserves. The Kauhale Preserve (below) includes a federally protected Wetland Preservation Area, which provides vital nesting grounds for the endangered Ae‘o (Hawaiian Stilt), Alae Keokeo (Hawaiian Coot) and Koloa Maoli (Hawaiian Duck).

Visit the Hoakalei Cultural Foundation to learn more.

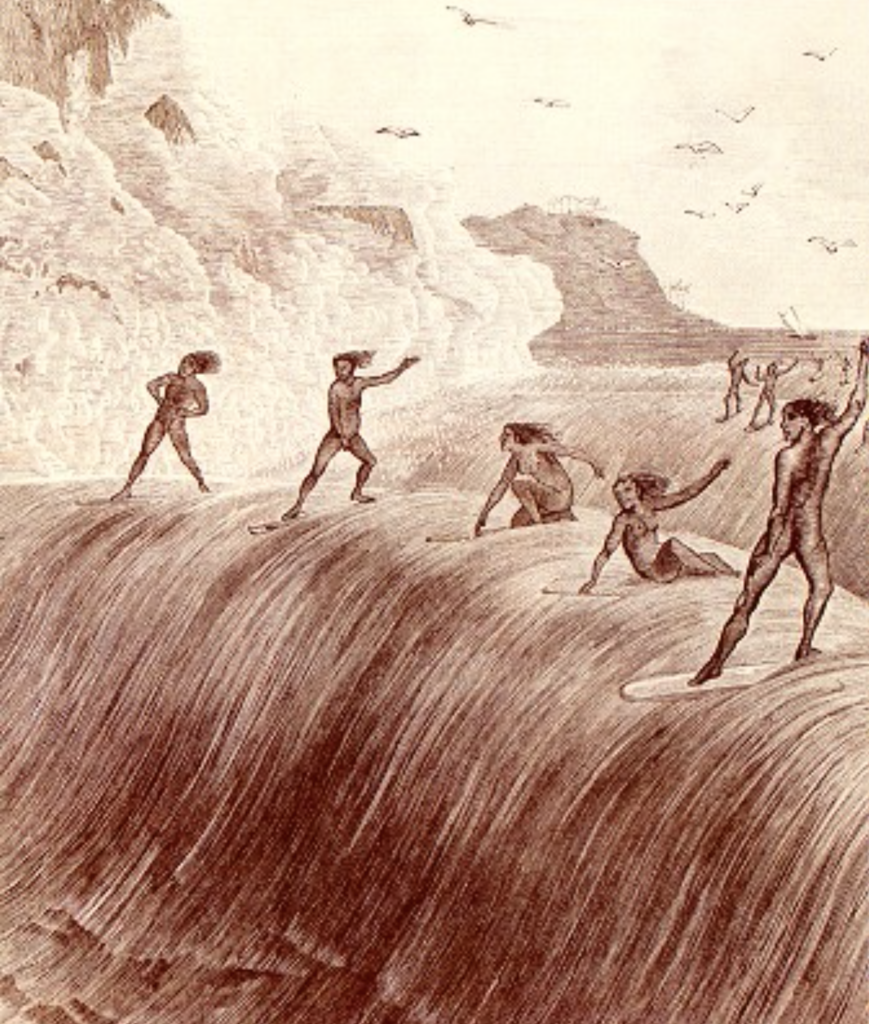

Heʻe Puʻewai (River Surfing)

Heʻe: to Slide

Puʻe: referring to turbulence

Wai: indicating the medium of fresh water

Although Hawaiʻi is commonly known as the birthplace of surfing ocean waves (heʻe nalu), there were actually six traditional surfing sports performed by Native Hawaiians going back to antiquity, one of which is river surfing. This is documented in historian John Clark’s 2011 book, Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions from the Past. The section dedicated to river surfing is largely based on passages Clark gleaned from nineteenth and twentieth century Hawaiian-language newspapers and English-language period literature. These verify that as with all things surfing, it was Hawaiians who first elevated surfing on stationary river waves to the level of a national sporting practice. Citations specific to heʻe puʻewai warrant a firsthand read by serious students of the sport’s history.

Clark’s research confirms that Native Hawaiians river surfed on no less than four of the Hawaiian Islands, including Waimea River on Oʻahu, Wailua River on Kauaʻi, Wailuku & Waiohonu rivers on Maui, and Wailuku, Honoliʻi, Papaʻikou, and Waipiʻo rivers on the island of Hawaii. The most notable to this day is the mouth of Oʻahu’s Waimea River, where a resurgence of river surfing has occurred among the locals and lifeguards on Oʻahu.

Multiple references to Native Hawaiians surfing on stationary waves on rivers, streams, or the places they meet the sea by Native Hawaiians are cited in M. Puakea Nogelmeier’s 2006 translation of The Epic Tale of Hi’iakaikapoliopele. Nogelmeier’s translation of the legend as it was originally published as a daily series in the Hawaiian-language newspaper Ka Na’i Aupuni in 1905 and 1906, highlights several incidents where river surfing is mentioned as they journeyed across our island chain. Hiʻiaka fondly remembers men and women surfing the river mouth in Hilo on Hawai’i Island in her tale. Later, on her return journey going to her sister Pele’s home on Hawaiʻi Island, she aggregates chants calling for the death of the ruler of Maui, ’Olepau, where multiple times she references “The women who surf the river channels.”

In particular, heʻe puʻewai was made famous in this ancient tale through the story of Piliaʻama and Kapuʻewai of Waimea Bay. While some Hawaiians were surfing their long olo and kīkoʻo surfboards on the giant waves out at the point, Piliaʻama was a local chief who was well known for “heʻe puʻewai,” surfing the mouth of a stream when it broke through the sands, and “heʻe puʻeone,” surfing the huge shorebreak and skimming along the wet sands at the shoreline. His high-ranking lover was named Kapuʻewai for the swirling waters where the stream (wai) and sea (kai) meet, creating “agitated” swirling waters. These waters can even form a whirlpool from the interaction of the different densities of fresh and saltwater, a phenomenon that is both beautiful and dangerous. Now Piliaʻama is forever immortalized as a stone along the side of the highway, a patron deity upon which to heap thanks and request blessings in the surf at Waimea Bay. He is a crab-shaped boulder about 3 feet tall by four feet long, with his large footprint stamped atop it–a depression for offerings at the stone.

Piliʻaʻama is described as a magical moʻo (lizard/dragon/shapeshifter) and fisherman, konohiki (overseer) of the lower valley area called Ihukoko. HIʻiaka and her companion Wahineʻōmaʻo addressed him as they passed by Waimea Bay, asking for his fish, the ʻoʻopu poʻopaʻa. However, he refused them, retorting rudely to catch their own fish, then dashing up the cliff due to his fear of the radiant goddess. Just as he went to transform back into a moʻo, she turned him to stone as well, leaving his last leaping footprint atop the stone. Today this stone is recognized by the Hawaiʻi Historical Society as one of the most endangered cultural sites on the island due to its proximity to Kamehameha Highway and location along the cliffs.

Clark cites an 1822 English-language journal entry by early missionary William Ellis, who describes Hawaiians surfing the “agitated water” at the mouths of flooding rivers. He also cites a September 1913 issue of Mid Pacific Magazine, John Cummins reminiscing about an 1877 tour he took around Oʻahu with Queen Emma, the wife of the Hawaiian sovereign King Kamehameha IV. Cummings was determined to “give Her Majesty and her party a view of this ancient sport, alluding to the earliest beginnings of he’e pu’ewai.

Cummin’s workmen dug a trench to open a beach pond (muliwai) at the mouth of the Pūhā River in Waimanalo, Oʻahu. Two women and two men demonstrated their he’e pu’ewai skills for the Queen and her party. The most skilled among them body surfed back and forth on a wave face while holding up the tip of his malo, a traditional garment worn by Hawaiian men. Other references appear in Clark’s book as well, along with a wealth of knowledge about heʻe nalu, truly a traditional Hawaiian cultural activity.

Hawaiian cultural practitioner Tom Pōhaku Stone shared how he and other Hawaiian keiki capitalized on standing waves that they discovered in rivers and streams to he’e pu’ewai on their “papa uma” (board used under the chest) or papa pāhā (a small board that could be used kneeling or prone and standing on Oahu rivers and streams throughout his childhood in the 1950s.

Legendary Hawaiian big wave surfer, assiduous life saver, and heroic Polynesian voyager Eddie Aikau, and his accomplished younger brother Clyde Aikau were avid river surfers on Oʻahu’s Waimea River in the early 1970s and possibly earlier, as were other North Shore Water Safety Officers (aka. Lifeguards). Legendary lifeguard Mark Dombroski tells of bodysurfing the draining Waimea River with Eddie Aikau as early as 1972 or ʻ73.

We may never know when river surfing outside Hawaiʻi began. Surfers are by nature an inventive lot, particularly when they happen upon surfable waves in their travels. The prevailing global narrative has been that river surfing started in Germany when Arthur Pauli first stood unsupported on a surfboard on Flosslände, a river wave on the Isar River in Munich on September 5, 1972. Around that same time, fellow Bavarian adventurers were “Brettlrutschn” (board-sliding) on small bodyboard-sized wooden boards tied with ropes to the bridge at the Eisbach, a famed river wave in downtown Munich. They soon discovered they too could surf the wave without need of a rope. According to urban lore, people have been stand-up surfing there since the city dropped concrete in the channelized waterway in 1972, and they say that city residents were Brettlrutschn there well before that, but without the bottom contours created by the concrete, it was a fickle wave. In fact, the Pauli brothers were first to ride unsupported, without aid of a rope, on Flosslände, a completely separate wave on the Isar River some miles away from the Eisbach in Munich! Brettlrutschn had uncertain origins, but it has been practiced on Bavarian rivers since the mid to late-1960s, pretty much anywhere a suitable bridge or tree was available to tie a rope off too. Now this man-made river feature is famous worldwide, and surfers wait in line to surf it one at a time!

It appears that the German and North American origins of the sport arose separately, as neither had any knowledge that river surfing had arisen elsewhere. North American river surfing history traces through Mike “Fitz” FitzPatrick, Steve Osman and Steve Hahn, who first surfed the Lunch Counter Wave on the Snake River in 1978. Fitz learned to surf on the East Coast, then lived and surfed in California, and later got pretty good in Tahiti. River guides Fitz and Osman had talked about the Lunch Counter primary wave’s surf potential in 1976 and 1977, but they lacked a surfboard. In 1978 they discovered that a fellow guide, Hahn, had a board and had tried surfing it without success. They convinced him to share, and all three met at the Lunch Counter one day after work in 1978. Being the most experienced, Fitz was the first to get to his feet. It took the others multiple sessions, but eventually they too figured it out.

Devotees to this new adventure sport began to spread throughout North America. As their stories and commentary began to appear in surfing and sports media, North American river surfers began to expand their river surfing experiences. New waves were discovered, new rivers were surfed, and small communities of surfers began to coalesce around better river waves. In the early 1980s, Ron Orton rode the Jordan River in Northern Utah, and later he competed and took first place in a contest at the Jordan River Hole in 1983. Notably, two unnamed Hawaiian surfers were regulars at the Jordan River Hole in Northern Utah in 1983, rolling up in their bright green & gold ‘57 Cadillac.

In 1985 and 1986, the Meistrell family of Body Glove International were invited to bring members of their team of professional surfers and body boarders to surf the Lunch Counter wave by way of longstanding business relationships and personal friendships with John Krisik and John Scott of Jackson, Wyoming. Snake River guides and practiced river runners – like Krisik, Scott, and first-ever North American river surfer Mike FitzPatrick – ensured there was river safety for professional surfers like Allen Sarlo, Brian McNulty, Jim Hogan Ted Robinson, and Scott Daley and professional bodyboarders Danny Kim and Ben Severson, raising the bar for all.

Seal Morgan and Don Piburn were the first to board-surf the Big Kahuna Wave on the Snake River in 1989. Tony Jovanovic was a BC-born Canadian and Snake River Wyoming local beginning in 1992. Jovanovic, pioneered multiple waves on the Snake River, the Loscha Pipeline on the Loscha River in 1996, and Upper and Lower Rock Island on the Columbia River in 1995. In 1999 river surfing crossed the Canadian border when Tony was the first to board-surf Skookumchuk Narrows in British Columbia, the most extreme tidal rapid wave yet discovered, and one of the most dangerous. Whirlpools and undercurrents abound in river rapids, thus these surfers that spread river surfing deserve due credit for developing water safety protocols, just as surfers and lifeguards did upon oceanic shorelines the world over.

A culture of surfing grew wherever these river waves existed, and embedded within it, these new communities of surfers shared their stoke and their aloha upon these stationary waves. No matter where surfing exists, it's wonderful that the surfers are coming from a place of aloha. In an International River Surf Magazine called Riverbreak, author Don Piburn, an early Wyoming River Surfing Pioneer former 1970s skateboarder, and 1980s snowboarder who has lived on Oʻahu for over 35 years, puts it best:

“Locals, traditionally the river runners, but progressively generations of river surfers, understand how to access, enjoy, and safely exit river waves. They know local rivers in all seasons, water levels, weather conditions, and complexities. They are there for big water spring runoffs, midsummer play days, and enduring low-water conditions. They watch out for the safety of the less-experienced. They develop complex relationships across years of shared sessions and uncommon adventures. They transmit local knowledge, techniques, and style. They tell and retell local stories. They build river cultures that enhance river environments and boost local economies. Communities of river sports enthusiasts spring up around good waves, and community is everything!”

Now communities of surfers are growing in land-locked regions where wave parks have been built, giving newcomers to the sport the opportunity to surf. The technology allows for many types of waves to be created, with the LineUp at Wai Kai bringing forward a unique tradition from the ancient past that has caught the world by surprise as a valid modern pastime. Wai Kai thanks Don Piburn for his dedication to supporting us with the documentation and story telling of the History of River Surfing.

The tradition of heʻe puʻewai continues on rivers around the world and in Hawaiʻi, such as the photos below of Waimea River mouth after heavy rains break the sand bar show. Indeed, many Oʻahu river surfers wait patiently for the call that the beach face berm at the Waimea River Mouth has been cleared. Now, surfing a stationary wave can be mastered by beginners and experts alike!

The Wai Kai Wave, powered by citywave®, will be Hawaii's first "man-made" deep-water standing wave at 100 feet wide and adjustable from two feet to head high, offering an authentic surf experience for everyone from beginners to pros. With the ability to control both the flow of the water and the angle of the reef below the surface, the Wai Kai Wave brings the historical sport of heʻe puʻewai to modern Hawaiʻi for all to enjoy, 365 days a year. Come join us to experience heʻe puʻewai at Wai Kai, or just enjoy the waterman lifestyle on the lagoon where many ocean recreation activities are offered for the whole family.